What is agrarianism and where does it come from? Agrarianism involves a “faith in agricultural economics, an affirmation of rural communalism, and a conviction that farming was indispensable to those qualities that made the nation unique.” During the Cold War, this ideology became purposed towards anticommunist efforts. But it has earlier roots. In Japan, agrarianism appears to have become prominent towards the end of the 19th century. Such ideals became part of its imperialist expansion into rural regions of Northeast Asia in the build up to, and during, the Second World War.

But what about Southeast Asia?

Soon after the Second World War broke out in the Pacific in December 1941, Japan adopted a series of policies for what it called the Southern Areas. The Southern Areas were divided into two. Area A included the Dutch East Indies, British Malaya and Borneo, and the Philippines. Area B was comprised of French Indochina and Thailand. Places designated in Area A appeared the prime initial focus for resource extraction, especially oil, natural resources, and food.

Let’s consider Java as an example. For feeding the war machine, agricultural production on Java was crucial. Colonial forces implemented a neighbourhood system (tonarigumi) used in Japan to better mobilize people for production and monitor them for subversion. This system was utilized to coerce production and supply food, especially rice, for the war effort. The practical dimensions of agricultural extraction during the occupation is well-understood. The ideological dimension, to my eye, seems less so.

Recently I came across copies of Djawa Baroe (New Java), an Indonesian language Japanese propaganda magazine published during the War. There are numerous insightful articles and photos within its issues. I thought putting up images of some that seem relevant to agrarianism here could be worthwhile to keep myself posting.

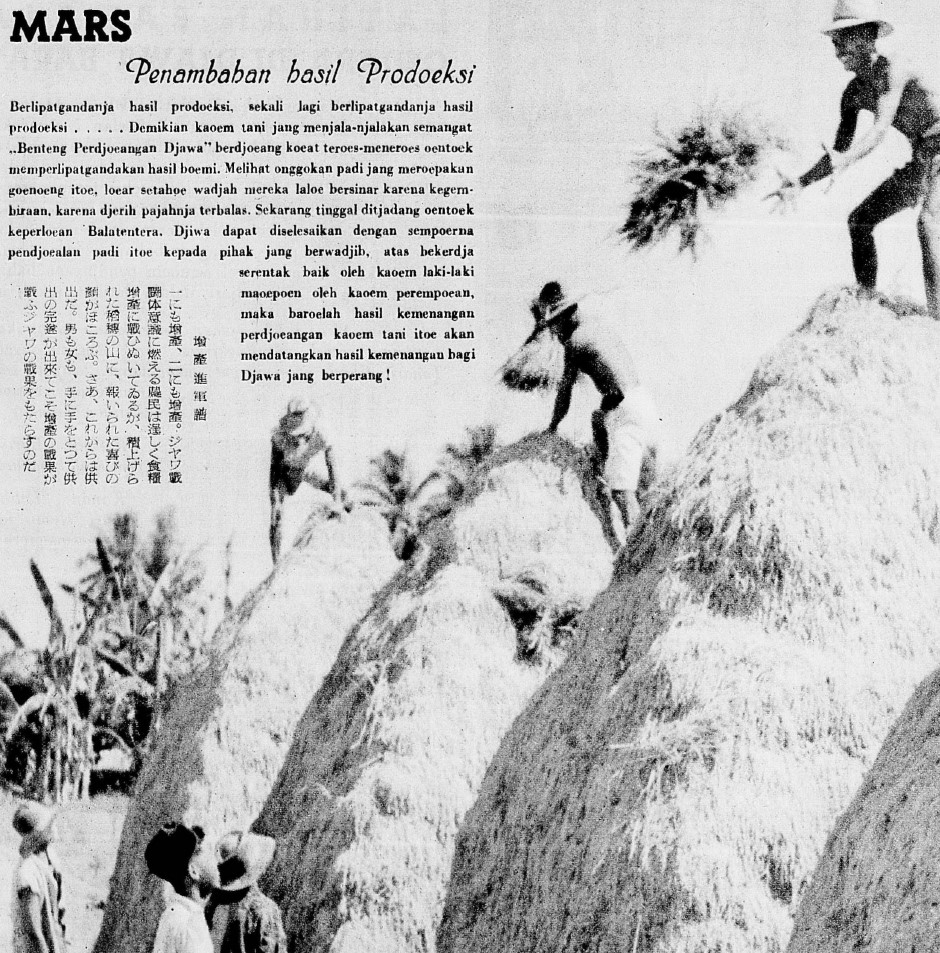

This one of men standing atop mounds of rice is from the 1 August 1944 issue. At that time, Java was undergoing one of the worst famines of the 20th century (which receives comparatively little attention). A rough translation of the text reads:

Ever more results from production… With it, the peasants’ spirits were ignited. “Java’s Fortress of Struggle” fights hard to improve the Earth’s yield. Their faces continually shone with joy because their colonial toil was rewarded upon seeing rice mounds that were like mountains. Now it will be stored for the needs of the Army. With the concerted efforts of both men and women, their souls could be completely satisfied by selling the rice to the authorities. Only then will peasants’ triumphs in such struggles bring victory for Java’s war!

Although it may be the case agrarianism in Indonesia and elsewhere in Southeast Asia was prevalent before the Japanese occupation, the war was a critical period for state formation. Identifying Japan’s agrarianism during the occupation could be helpful to discern its influence relative to pre-occupation variants. Giving greater attention to ideologies concerning agriculture and rural life instilled during key junctures of state formation can also be useful for better understanding the long run consequences on countries’ agrarian politics and how, if necessary, to address them.